The Bible.

What does it teach?

What are it’s most important principles?

One passage can mean something to one person — and an entirely different thing to another.

In fact, both Jesus and Paul made a habit of quoting old Scriptures and using them in ways the audience had not thought of.

Is it dangerous to look at Scripture that way? Or is the right way to dive in to the word?

Consider, for instance, the passage concerning the Bereans who “searched” the scriptures (Gr: writings).

The more accurate translation of “search” is actually “to scrutinize.”

Is it a good idea to scrutinize the writings?

The people in Acts are commended as noble for doing so. They apparently took no message at face value — and neither should we.

Maybe there’s another passage that demonstrates how we should look at “the writings.”

“Study to show thyself approved to God…”

What does a more accurate translation of this passage look like?

Be eager, fully approved to present yourself to God as an unashamed worker [or teacher], rightly dividing the word of the truth.

In the Greek, does this passage mention studying? (No). Or to do something to demonstrate approval to God?

No!

In fact, the word approved means “been tested” and some translations include ~[tested by trial]~ in parentheses to help clear up the meaning of approved, there.

Further, the idea that God is swayed by outward demonstrations of faith would contrast with the context of the rest of scripture — for God looks to the heart.

No — the sentence reads without a mention to studying and the word “approved” means we’ve been “proven” through our trials. And because of this?

Be eager — you are fully approved by God. You can live with full vigor — entirely free of shame or guilt. You can dissect and understand truth.

Let’s jump past the good news of this passage (eager, proven, no shame) to the part about truth.

We must — we have to — use reason to dissect words of truth.

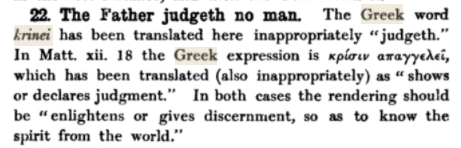

An eager biology student does not approach the dissection table, make no cuts, and proclaim the job done.

In the same way, the writings are meant to be chopped, explored, and thought about. We must see what’s inside the word.

The Greek word for “rightly divide” is orthotomounta and it means to cut straight. But how can we cut straight without practice?

We must be perpetual biology students, dissecting the word from the inside — and never read the Bible as a rule book, which requires little dividing, but rather, only obedience.

How can this be — and how does it work for the investigator of truth? Let’s explore deeper.

Paul is traveling through ancient Greece.

When Paul sees the idols in Athens, something happens. Some translations say he became angry, but most tone down his feelings.

The Greek word in question is paroxynato — meaning (according to Strong) to be aroused to anger, but the word also has other notions such as “to provoke” (especially with regards to anger).

Let’s observe how different translations interpret Paul’s reaction differently:

KJV

Now while Paul waited for them at Athens, his spirit was stirred in him, when he saw the city wholly given to idolatry.

Acts 17:16 (KJV)

NIV

While Paul was waiting for them in Athens, he was greatly distressed to see that the city was full of idols.

Acts 17:16 (NIV)

TLB

While Paul was waiting for them in Athens, he was deeply troubled by all the idols he saw everywhere throughout the city.

Acts 17:16 (TLB)

DARBY

But in Athens, while Paul was waiting for them, his spirit was painfully excited in him seeing the city given up to idolatry.

Acts 17:16 (DARBY)

AMP

Now while Paul was waiting for them at Athens, his spirit was greatly angered when he saw that the city was full of idols.

Acts 17:16 (AMP)

In all of these translations, despite anger being a legitimate and primary meaning of the Greek word, most translators decided to use different words to describe how Paul felt. Many different words.

One side point to consider from this story:

Anger, frustration, and passion are acceptable in response to error — especially error that harms people.

This is not to say that anger yields results — it usually has the opposite effect of closing people’s ears and hearts to a message.

But the feeling in response to persistent problems is legitimate. There are plenty of other examples of this throughout the Bible — and logic supports this concept, too (as does modern psychology research). To withhold or suppress these emotions is unhealthy across the board.

If we are to support those who are angry, it is first to acknowledge any and all emotions as legitimate.

Paul then laid out the good news to the people listening in Athens.

A point of interest:

- The “heathens” were interested in hearing his ideas, and for the most part respected him.

Perhaps we can be inspired by those who were willing to learn and grow in matters of truth, challenging their long-held notions when presented with reasonable evidence.

Paul’s Good News

The essence of the true good news is this: That God wants all humans to be close with him (not just Israel), to walk in spirit (righteousness) — and to turn away from things that aren’t good and lovely (repent).

Paul begins:

God did this so that they would seek him and perhaps reach out for him and find him, though he is not far from any one of us.

Acts 17:27

Look at the word “seek.”

The Greek word is zetein — which means “to seek,” but also “desire” or “demand.”

Look at the phrase “reach out for.”

The word in Greek is pselaphaseian which actually means “to touch” or “to manipulate” with a hint toward “to confirm (by feeling or touching).”

For example: In early childhood education, small toys that facilitate the development of dexterity in the hands and fingers are denoted “manipulatives” — and each class is required to have them.

Is Paul saying people will reach out for God… or touch God? Potentially these are two incredibly different connotations — one suggests a gulf between man and their God, the other suggests intimacy.

Let’s see how this passage looks with the more literal translation of pselaphaseian (and an alternate meaning for zetein).

God did this so that they would desire him, perhaps touch him and find him, though he is not far from any one of us.

Acts 17:27

Consider the word “though.”

It’s a curious translation to English, here — the word is a negative adverb that means “however.”

But in the Greek, it’s possible that a more literal translation of the word is “indeed” rather than “though” (this word tends to be used as a point of emphasis).

When the passage is viewed in this more literal way, it actually becomes one unified idea, without a need for a juxtapositional “however.”

God did this so that they would seek/desire him, perhaps touch him and find him — for indeed he is not far from any one of us.

Acts 17:27

Let’s explore a few verses further and look at some more translation choices — choices that cause many to be unable to imagine that God’s “good news” is actually, truly good.

Here’s a common English translation:

In the past God overlooked such ignorance, but now he commands all people everywhere to repent. For he has set a day when he will judge the world with justice by the man he has appointed. He has given proof of this to everyone by raising him from the dead.

Acts 17:30-31

Look at the word “command.”

The original Greek word: parangellai (to notify, command, charge, or entreat). Each of those are INCREDIBLY different meanings. To entreat someone — or to “earnestly urge” — is very different than “command.”

God urgently urges us to come and see that he is truly good, and that he is gentle.

Now let’s look at the word “judge.”

The original Greek word: krinein. Literal meaning: to separate, sift, divide, or arrange. More figuratively, the word could imply meanings such as “to judge,” or “to criticize.”

Even Christian concordances say that the proper definition of this word is to distinguish, but “by inference,” the word means “condemn, judge,” etc. This is a very different meaning than the most literal definitions of the word. I also think there’s an element of “to see correctly”

Then look at the word “justice.”

The Greek word is dikaiosyne. Dikaiosyne most literally means “with equity, especially in terms of justification.” Justification means “the action of showing something/someone to be right or reasonable.”

Making things justified & right, arranging things.

Now that sounds like a Savior, a rescuer.

So the phrase that reads traditionally: “For he has set a day when he will judge the world with justice“ has an incredibly different tone and meaning from the more literally translated: “For he has set a day when he will arrange the world with justification“

So if we use more literal translations — the more literal meanings — this passage begins to read differently:

“In the past God overlooked such ignorance, but now he urges all people everywhere to repent (literal meaning: to turn away from bad actions). For he has set a day when he will arrange the world with justice (better translated “justification”) by the man he has appointed. He has given proof of this to everyone by raising him from the dead.”

Acts 17:30-31

Now look at that word: “proof.”

Would it surprise if this translation could be improved — or made more literal? The Greek word is pistin which means faith, confidence, or guarantee. Not “proof” –> with the burden on us to agree with the evidence.

Let’s see how this passage reads, now:

“In the past God overlooked such ignorance, but now he urges all people everywhere to turn away from bad actions. For he has set a day when he will arrange (or decide) the world with justification by the man he has appointed. He has guaranteed (or provided faith) to everyone by raising him from the dead.”

Acts 17:30-31

It is entirely reasonable, if not incredibly convincing, that this is more accurately represents what Paul actually said to the people listening to him.

So far, we’ve been looking at pivotal words and seeing what happens when translated more literally.

What’s interesting is that there is a curious trend throughout Biblical translations: It seems translators go out of their way to describe God as angry and condemnatory — even as they go equally far to make Paul seem not angry (only concerned, moved in spirit) by the idols of Athens.

Why might the translators work hard to make God appear angry — using implied meanings rather than literal — and do so with such regularity? Why work hard, in reverse, to make Paul appear thoughtful and kind?

Many books have been written on this very subject, with likely culprits for this trend being the influence of Augustine on the translations of books that became the Bible, the fact that most first translations to English were from Latin instead of the original Greek, as well as the slow creep of paganism into Christianity.

In fact, in nearly every passage of scripture with dark undertones, the more probable and logical translations of the heaviest words have been ignored — left for translations that fit a troubling narrative espoused by Christianity since the time of Augustine. When we follow the more literal translation, things fit — line up, even — with a much more loving and less vengeful, exclusivist God.

Remarkably, most of the time, concordances say that the more scary/angry interpretations are implied meanings — while the unused, more literal definition of the words are quite more positive, uplifting, uniting, happy, encouraging, and good.

For clarity:

- To imply is to hint at something, but to infer is to make an educated guess.

- The speaker does the implying, and the listener does the inferring.

- To imply is to suggest something indirectly. (Source).

Can it possibly be that God’s wrathful nature is often only implied throughout the text? That is, it must be inferred by the reader?

Of course — simply reading an English Bible, one can’t discern whether the translation uses an implied meaning or a literal one.

There are obviously thousands of passages with words like these peppered throughout the Bible.

In each of the passages that use terminology appearing to support the concept that God is keenly focused on hell, punishment, fear, and judgment, go back to the original Greek. Look for the more common, typical, and literal meaning of the word. Chances are, you’ll see concepts more fitting with love, restoration, and reconciliation than damnation and wrath.

Consider again the translation of Paul’s emotional reaction to the idols in the city: equally valid meanings of the word paroxynato are “irritated, exasperated, provoked.” He felt something. It’s impossible for us to accurately know whether he was more “fuming with anger” or “deeply and passionately bothered.” It’s impossible for us to know based on the Greek word.

And yet, when we see the “wrath of God” phrase in the Bible, we don’t question whether there’s a translation error. But should we?

God makes way more sense — he’s actually, truly good — when we use the better, more true translations. At some point, it makes sense to say: “Huh. The entire theology of God being terrible is a poor translation.”

It’s so easy to proof-text — to string together all the scary ideas we’ve heard for so long, pulling one verse from here, one from there — each poorly translated, until we can’t possibly imagine God differently than the way we’ve been taught. In truth, we’ve likely heard these concepts since childhood: dividing the world, demanding rules be followed, punishing, angry.

Let’s move to Romans 3:5-8.

Look at the word “wrath.”

Greek word, origen, literally means “desire” or “passion.” It literally means “to swell.”

But if our unrighteousness brings out God’s righteousness more clearly, what shall we say? That God is unjust in bringing his wrath on us? (I am using a human argument.) 6 Certainly not! If that were so, how could God judge the world? 7 Someone might argue, “If my falsehood enhances God’s truthfulness and so increases his glory, why am I still condemned as a sinner?” 8 Why not say—as some slanderously claim that we say—“Let us do evil that good may result”? Their condemnation is just!

Romans 3:5-8

Look at the word “judge.”

The Greek word is krinei and it’s lacking the prefix that can modify it to the negative meaning. Therefore, it’s a neutral term and reflects awareness and knowledge (discernment) rather than anything negative or condemning. Look at the word krinesthai which means to “explain.” Krinei seems to suggest more seeing what’s true and deciding what’s true (discernment) — and what must happen — than anything.

Look at the word “condemned.”

The Greek word is krinomai — meaning “decided,” “denoted” or “designated.”

‘But if our unrighteousness brings out God’s righteousness more clearly, what shall we say? That God is unjustified [or: incorrect, unreasonable] in bringing his desires on us? (I am using a human argument.) Certainly not! If that were so, how could God arrange the world? Someone might argue, “If my falsehood enhances God’s truthfulness and so increases his glory, why am I still designated as a sinner (alternate: detestable)?” Why not say—as some impiously claim that we say—“Let us do evil that good may result”? Their designation as a sinner is just!”

Romans 3:5-8

The argument is never about heaven and hell. Back then, the context was about which god was right.

The idea that Yahweh (the rescuer) was correct was the argument of the day — against all the gods of the region.

Under Roman occupation, the surrounding tribes made war less with the Jews. In its place, the nexus turned to more discussion of ideas, and searching for truth. Religious sects were ubiquitous, with daily disputes in all temples and common areas. This is why the idea of God’s “discernment/ascertainment” is so important in all these conversations.

It’s unfortunate that the primary concept taken from these passages in modernity revolves around “judgment.” Especially when we consider the word judgment is inherently a neutral word.

The word should mean that the one, true God was the ultimate God, and the truth was in him. His words are truth and are worth following, rather than the little daemon spirits the surrounding regions put their hope in.

The message of judgment is not that God has come to divide mankind into sinner/saved, but to unite the world away from confusion and division and onto the best paths with him.

Any thought of condemnation for sin is put to death — for all ages. Now free, go live in spirit, in unity with God and all the universe.

The Good News Sounds REALLY Good

→ Notice that many people were mocking Paul’s teaching because it really sounded to them like he was saying people everywhere could sin freely. This is important — that’s exactly what the good news sounds like.

In fact, the pagans were criticizing Paul for making it sound like they could do bad things. That’s insane!

Whenever “that Day” is referenced as coming, it’s so commonly referred to “…and now is/already has happened.” We almost ubiquitously see a blending of time and space, into the ever-present now. The great I AM is not of the future or past.

1 Thessalonians 5:9

For God did not appoint us to suffer wrath but to receive salvation through our Lord Jesus Christ.

1 Thessalonians 5:9

The context of this passage is about not giving over to wreckless passions like being unaware — figuratively, asleep and drunk — but instead to put on the characteristics of Spirit: faith, love, as well as the hope of security and rescue from trouble.

How do we know the context of this verse? The verses before it: Paul talks about people being spiritually asleep, and being drunk, and says that’s not who we are — given over to passions (orgen) — but instead to be sober, finding safety in Spirit.

Look at the word: “receive.”

The Greek word is: peripoiēsin meaning to “find” or “acquire” or “own.”

Even the word appointed (etheto) can simply be read as: to lay, to put, to set up.

God didn’t design things — or put things, or lay things out — in a way that we are given to mindless passions and escapism from our troubles.

What would a more literal translation look like?

For God did not put us here for those passions (or desires; literally: to swell) but to find security through our lord Jesus Christ.

1 Thessalonians 5:9

Let’s ask a similar question: Is hell a biblical concept?

The answer? No.

Hell — as we know it — is not in the Bible.

Well, at least, not in a literal translation of the Bible.

Why the discrepency?

Let’s explore this.

Many Words Are Translated To Hell

Four words are translated into hell in the Bible:

Sheol

The Old Testament uses sheol exclusively.

- Sheol is used 62 times.

- Sheol was a place under the ground where the dead slept.

- Sheol is not hell.

The New Testament mentions gehenna, hades, and tartarus, only.

Tartarus

Tartarus is only mentioned once (2 Peter 2), it’s where rebellious angels were sent to await judgment. It is not a place humans go, nor is it a place anyone goes after judgment.

Tartarus is not hell.

(More thoughts about 2 Peter 2)

This logical appeal is also used simply to warn that manipulative, evil teachers will rise up, and they will be hypocritical — using counterfeit words to exploit people.

This passage says God does not wink at such “teachers.” (If God physically killed women and children in the old testament, these teachers deserve the same).

Keep in mind: This passage is essentially saying that God physically rescues the righteous from present-day challenges and punishes the wicked with challenges in life — a common theme throughout the Bible that conceptually contradicts with some of Jesus’s teachings (John 9:3, for instance) and modern-day thought.

Hades

Hades is also mentioned in the New Testament 11 times, but it’s decidedly referring to a waiting place for the dead — after which there will be a resurrection.

“The gates of hell shall not prevail” is a mistranslation. More accurate: “The gates of hades (or death) shall not prevail.”

Gehenna

Gehenna (The Valley of Ben Himmon) is a real, geographical place.

Where? A sewage and trash-heap immediately outside Jerusalem. A place of maggots and filth. It burned continually, 24/7, to combat the excrement and decay.

It was also where:

- child sacrifices happened hundreds of years before Jesus.

- dead bodies were dumped, especially of the poor.

(Isaiah describes the Valley of Gehenna)

In Isaiah, the prophet says that the enemies of God (the surrounding tribes and nations) will be defeated and their bodies will fill the place where the Jews put dead bodies. In fact, their war success would be so great, and there would be so many bodies that worms would never die and the fire would burn perpetually. It’s an apocalyptic message for the nations Israel was constantly at war with, and from whom the Jews were always pleading with God for salvation from.

By Jesus’s day, Gehenna had long been the valley where trash was burned and bodies of the poor were discarded.

Did the Jews of Jesus’s time think of our modern concept of hell when they heard Jesus talk about Gehenna?

Of course not, the Valley of Gehenna (or Ben Hinnom, named after a man) was not a park, or occupied at that time — it was a place of sewage, dead bodies, a perpetual trash-fire.

1 – Mocking Jesus

So when the Pharisees were mocking Jesus after he told a parable, he said, “Woe to you, for you obsess over converting one person, and make him twice the son of Gehenna that you are.”

A profound and, almost certainly, shocking insult to the spiritually elite, yes?

2 — Your Right Hand

What did Jesus mean when he said: “If your right hand causes you to stumble, cut it off and throw it away. It’s better to lose one body part than for your whole body to be thrown away (in Gehenna).” This visually — and powerfully — describes the way sin harms us when it persists.

3 — Preparing The Apostles

When Jesus was preparing the apostles for the difficulties to come — where they’d be constantly threatened with arrest and execution, he encouraged them repeatedly to not be afraid.

The passage’s focus is to not fear what people can do to you, for God is much greater and in control of both life and death, and even has power over the existence of souls.

(26 “Therefore do not fear them… 28 Do not fear… 31 So do not fear…)

If we want to focus on fearing God, there are plenty of passages that inform us we should not fear him, either. Jesus has a point to make, and it’s not to scare his apostles.

Jesus does not say God will destroy souls, but that he has the power to – and this is a reason to not be afraid. This is entirely consistent with the idea that hell does not exist.

(More about God’s power to destroy)

Additionally, the ancient Jews saw God as controller of good and evil — and that bad thing happen because God wanted them to — and as direct punishment (1 Samuel 2:6). Modern people don’t quite think this way so much, anymore. Fear him who can destroy everything? Sure he can, but this isn’t remotely a new doctrine about what God will do — at all.

Lamentations 3:38 & Isaiah 45:7 — God manifests both good and evil. He is the decider. He decides who gets what, and how things go. He decides who is saved from calamity. The story of Job demonstrates this.

Devout Jews to this day sometimes debate whether the Holocaust was God-controlled against the Jews. This closely aligns with ancient thinking about God, the decider of what happens, the controller of both good and evil.

4 — You Fool

What about when Jesus says that the words “you fool” make you “guilty into the fiery Gehenna”?

Check out Bill Muehlenberg’s explanation of this “problematic Bible passage.” As he says, this passage is “all about the context” — and it’s a typical commentary on this passage.

(Muehlenberg’s thoughtful answer)

There are two main reasons why this passage is problematic: it seems to forbid something which is done elsewhere in Scripture, and it offers a very strong penalty for something which does not seem that bad. It has to do with using the term “fool” against other people. The last part of this passage says, “And anyone who says, ‘You fool!’ will be in danger of the fire of hell.”

A lost eternity simply for calling somebody something unpleasant? And didn’t others in the Bible use the very same term? On both questions we can offer some explanation to resolve these apparent difficulties. The first and main consideration to raise here is that which helps in many such cases: consider carefully the context.

And the context is this: Jesus wanted his listeners to know that our outward sins are basically reflections of inward evil.

https://billmuehlenberg.com/2018/12/27/difficult-bible-passages-proverbs-264-5/

Something else to consider for Mr. Muehlenberg: These “difficult passages” aren’t so difficult if we realize Jesus is teaching deep truths about matters of the heart and pertinent insights for real people. Rather than being difficult passages — incongruent with surrounding text — they become enlightening, motivating, and full of power to change us.

Context is the Key to Understanding

Verily I say unto you, we should read the whole Bible like Muehlenberg reads the “you fool” passage. Read all passages with understanding of the context.

In fact, you cannot go wrong by looking for context. The more context you bring into a passage, the better you’ll understand it — or anything in life.

The more you know about a person, the better you understand them.

In truth, to read for context is to read for understanding. This is one and the same as to know the point of what’s being communicated.

Considering a passage’s context does not equate “picking and choosing what you like.” Context unlocks the true message of a passage.

In fact, without context, the message of the passage can be partially or entirely lost.

Jesus is not saying it’s a sin or “damnable” to say the words “you fool.” Those are words said by Jesus and others in the Bible. He’s making a larger point — that as you do outwardly, so are you on the inside. Incredibly profound!

This is a message repeatedly made by Jesus in his attempt to show that the state of mind is just as important as action.

There’s always more unity between body and spirit than we might think — and as we become aware of that, we become truly capable of good. We may also be startled by what we find in ourselves!

Instead of making good decisions blindly — or with reservation — make them from a unified spirit that sees the big picture.

He’s telling the listeners to be all in on being good.

For example:

“Whoever looks upon a woman…” This is another instance where Jesus takes the “law” and demonstrates that the law is not about actions alone, but rather that actions can reveal the state of the heart — something we should care about even more.

Now, if we read the “you fool!” passage without thought of context, we’ll have no choice but to formulate a religious belief stating that certain words are damnable — on their own. This, of course, would be an error.

It is good to use our thinking brain and logical faculties to reason that it is not, irrefutably, a sin to say the words “you fool.”

Likewise, to take the 15 verses that appear to refer to hell (in English translations) — and read them out of context — we’ll have no choice but to suspect Jesus introduced new concepts about hell.

Hell as a Clear Concept

We’ve established that hell is referred to 54 times in the KJV translation, but only 14 times in the NASB translation (which are all in the New Testament).

And of those 15 times, one is tartarus (definitely not hell), and the rest are gehenna.

Hades’s 11 occurences do not refer to hell.

Therefore, hell — conceptually — is referred to almost zero (if not truly zero).

How does that compare to other concepts in the Bible?

By contrast:

Again: How much does the concept of hell occur in the Bible? Virtually… none?

Here are the clearest references to hell:

Matthew 5:22 But I say to you that everyone who is angry with his brother shall be guilty before the court; and whoever says to his brother, ‘You good-for-nothing,’ shall be guilty before the supreme court; and whoever says, ‘You fool,’ shall be guilty enough to go into the fiery hell.

Matthew 5:29 If your right eye makes you stumble, tear it out and throw it from you; for it is better for you to lose one of the parts of your body, than for your whole body to be thrown into hell.

Matthew 5:30 If your right hand makes you stumble, cut it off and throw it from you; for it is better for you to lose one of the parts of your body, than for your whole body to go into hell.

Matthew 10:28 Do not fear those who kill the body but are unable to kill the soul; but rather fear Him who is able to destroy both soul and body in hell.

Matthew 18:9 If your eye causes you to stumble, pluck it out and throw it from you. It is better for you to enter life with one eye, than to have two eyes and be cast into the fiery hell.

Matthew 23:15 “Woe to you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites, because you travel around on sea and land to make one proselyte; and when he becomes one, you make him twice as much a son of hell as yourselves.

Matthew 23:33 You serpents, you brood of vipers, how will you escape the sentence of hell?

Mark 9:43 If your hand causes you to stumble, cut it off; it is better for you to enter life crippled, than, having your two hands, to go into hell, into the unquenchable fire.

Mark 9:45 If your foot causes you to stumble, cut it off; it is better for you to enter life lame, than, having your two feet, to be cast into hell.

Mark 9:47 If your eye causes you to stumble, throw it out; it is better for you to enter the kingdom of God with one eye, than, having two eyes, to be cast into hell. (ref to Isaiah 66:24)

Luke 12:5 But I will warn you whom to fear: fear the One who, after He has killed, has authority to cast into hell; yes, I tell you, fear Him!

James 3:6 And the tongue is a fire, the very world of iniquity; the tongue is set among our members as that which defiles the entire body, and sets on fire the course of our life, and is set on fire by hell.

2 Peter 2:4 For if God did not spare angels when they sinned, but cast them into hell and committed them to pits of darkness, reserved for judgment

If you need to ask this question, you’ve yet to find God.

You’ve yet to find Jesus — the real Jesus.

Do you need motivation to love others — apart from threat of punishment?

Do you need motivation to tell the truth — apart from threat of punishment?

Are you only faithful to your spouse… because you have to be?

If there is no hell, would you really go murder? Would you break into someone’s house and steal?

I can confidently say: You would do none of these things.

On the contrary!

If there is no hell, here’s what you’d do:

- You would pray.

- You’ll spend time in the word.

- You’ll be active in your church.

- You’ll forgive others, just as you are endlessly forgiven.

- You’ll teach your children to love, just as you are loved.

- You’ll make sacrifices for others.

- You’ll be a good steward.

- You’ll work hard.

- You’ll grow.

- You’ll be alert, awaiting that day.

- You’ll stand up for the poor.

- You’ll speak out against injustice and abuse.

- You’ll go to heaven.

Remember how many times the Bible talks about hell?

Virtually zero.

How much does the Bible talk about heaven?

Non-stop. Seven hundred twenty-seven times.

What does God want with you?

Do not fear, for I am with you. Do not anxiously look about you, for I am your God. I will strengthen you, surely I will help you, Surely I will uphold you with My righteous right hand.

euangelion: [Greek] — good news