The more you know about buildings, the better you’ll be able to find and build healthy buildings for you to live in.

As a general contractor (licensed/insured) I’ve been personally impacted by building health.

Here are five — pardon the pun — foundational characteristics to look for when examining the health of a building.

Roof overhangs don’t look very modern. But they do serve a purpose — a huge one.

They protect the building’s walls — and windows to some extent — from wind driven rain.

Why does this matter? Aren’t all exterior walls waterproof?

The answer is no, hardly! Exterior wall systems are designed to shed most of the wind-driven rain, but some will always get behind the cladding (siding). That’s why building codes call for a WRB (“water-resistive barrier”, like tar paper), which covers the sheathing (plywood/OSB) — to let water drain down and out of the wall.

When water gets behind the cladding, it shouldn’t soak into plywood sheathing. No, it should run down the WRB — and out of the wall.

It’s just a fact of building science that water will always find its way behind the cladding, and into the wall.

With “siding” (cement fiber board, vinyl, wood planks), there are obviously open gaps — between boards — in the wall, where wind can drive rain behind the cladding. These types of walls are best built with a “rain screen” (which is an air gap behind the siding) that allows water to drip down and out.

With masonry cladding (brick, stone, stucco), though, it’s not just wind-driven rain to worry about, but absorption of rain into the wall cavity. Masonry is porous! It absorbs moisture from rain, and humidity, too.

After a masonry wall absorbs moisture from rainfall, sunshine then drives the moisture inside the wall. If moisture can’t escape (weep holes at the bottom of the wall), it can become trapped inside the wall. That’s a very bad thing for building health (and yours)!

So, while a smartly-designed wall will allow water to escape (a good WRB + air gap + weep holes), it’s much better to prevent water from getting behind the wall in the first place.

And if you’ve ever looked at a brick wall after a good rain — and seen how dry a roof overhang can keep it — you’ll know how effective roof overhangs are at keeping your exterior walls dry. Less water on the walls means less water in the walls.

Roof overhangs also help keep water off of your foundation. Water is the enemy of any building’s foundation, causing the ground to shift underneath, or even soaking up into stem walls (causing moisture/humidity inside your exterior walls — not good). Every step you can take to divert water away from the foundation is an essential one. Roof overhangs do this quite well!

Windows are also protected to some extent by roof overhangs. Windows are notoriously leaky. It’s just a matter of time before windows will leak, especially cheaper ones. Unfortunately many, many windows are not flashed properly before installation, which would help divert leaks out of the wall. With poor flashing, when a window leaks, water enters the wall directly under the window. These leaks often take years or decades to appear visibly, but the moldy smells could begin much sooner.

How large of a roof overhang do you need? More is better, but a good rule of thumb is 18″ or more.

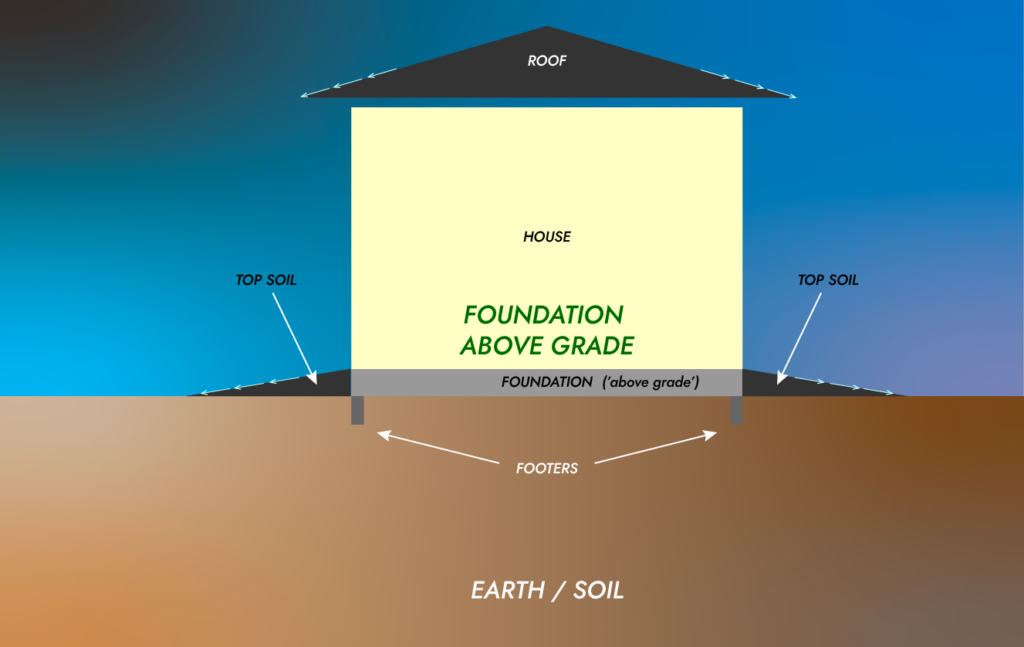

Speaking of keeping your foundation dry, the most effective way to achieve this is for the building’s foundation to be extend well above grade.

This may mean having to step up into the home — or using a ramp for ADA accessibility — but it also means the top of the foundation and first floor are set higher above the surrounding areas.

When the foundation is set high, it means water runs away from the house, rather than pooling up against the house (which will always cause major problems).

When you’re looking at a place to rent or buy, one of the first things you should know is the age of the building.

“When was this built?” should be one of the first questions you ask!

Why does the age of a building matter?

One simple reason: There’s been less time for moisture intrusion.

Leaks happen. Plumbing is never permanent. Strong winds blow. Big rains fall. Humidity rises. Water will always find a way inside the building, somehow, given enough time.

(Remember, with plumbing, water is already inside the building, in the pipes. It’s just a matter of keeping the water inside the pipes that is the challenge: Pipes fail, regularly, they just do, especially where they connect to fittings and fixtures (fittings = where two pipes connect with each other | fixtures = faucets, toilets, handles).

So the longer a building has existed, the more time has passed — and the more chances for problems to arise: pipes to fail, floods to rise, and rain water to find its way inside walls, windows, and more. During extended vacancy, even, humidity can rise to levels sufficient to support mold growth on all surfaces.

If I’m looking for a place to live, I look for buildings constructed within the past 18 months at the most, and I’d prefer younger than 12 months. This means I can move in and monitor things myself, watching for leaks, taking steps to prevent them, and keep the space clean.

I suppose I should mention, too, that a younger home also means less time for pets’ waste to soak into floors, or their dander to clog up HVAC systems, or for previous owners to otherwise neglect a space. If I’m buying a place, I’d rather avoid hidden surprises like that, seeing that they can affect air quality. There’s no way to know everything that previous owners and tenants have done, and what that might mean for your building’s health.

A major, major player in the health of any building is the HVAC system (or other air-conditioning / heating systems).

Any time air is forced through machinery, dust/pollen/microbes/spores can enter — and build up — in the system.

Unless you’ve got a MERV 11 or higher filter protecting the system, microbes and organic matter will collect inside.

Of course, when air blows over that organic matter, we breathe dusty, filthy air.

But that’s not the only problem — hardly. If there’s cooling inside the system, it means there’s condensation. Moisture.

(Heating can cause condensation as well, also leading to moisture in the system).

And any system that creates moisture can rapidly feed and support mold and bacterial growth inside the system.

Moisture plus organic matter will always mean microbial growth.

That’s why it is practically a guarantee for HVAC systems — installed normally — to begin growing mold within only a few years after installation.

The two biggest steps you can do to prevent mold in your HVAC system? UVC lights (installed at the evaporator coils) and a high-MERV pre-filter, installed on the return line. The pre-filter prevents organic matter and microbes from entering the system, and the UV light kills anything that might still find its way inside. A powerful one-two punch — at least for prevention!

But any HVAC system that doesn’t have those two components — or, at least, a UV light — will grow microbial life, and that can not only degrade performance, but cause sick building syndrome (and inflammation, or other symptoms of disease, long before the full syndrome develops).

Knowing what I know now — that it only takes a couple years for an HVAC system to begin to “turn” — means that when I’m looking for a place to buy or rent, I ask about the age of the house not only because of leaks, but also to know the age of the HVAC system.

Everything that’s true of HVAC systems is also true of ductless mini-splits: They still can become gross over time, and need to be fully cleaned, regularly. It is not common for mini-splits to have a UV light installed in them, yet.

Crawl space air will always become indoor air. In fact, it’s the primary source of your indoor air.

Why? Because first floors are not air-sealed at all. Not as much as modern exterior walls.

And crawl spaces are notorious for being damp, moist environments where mold often grows quite well.

Therefore, I would never buy a home that had a crawl space unless it was encapsulated. And hopefully, it was always encapsulated, since construction — before big problems could develop.

Similarly, basements are notorious for having moisture issues. It’s common for basement waterproofing to fail over time, or to be poorly installed in the first place. If basements are old enough — or you’re in an area where basements are uncommon (like mine!) — there may be zero waterproofing installed at all.

Therefore, I would almost never buy (or live) in a house that had a basement — unless I was confidant there had never been, and would not be moisture problems. And that’s a pretty tall order! It’s hard to look through dirt and see how things were installed.

There certainly are exceptions here. Some areas have better building codes and practices than others. For instance, there are plenty of northern climates where basements are extremely practical due to frost lines. These areas often have better waterproofing codes that protect basements. Doesn’t mean they don’t fail, though, which brings us back to the “age of the building” argument: I want less time for systems to fail when I’m buying/renting a house.

Garages almost always have unhealthy air. Whether it’s automobile fumes (even from new tires), lawnmower smells (gas, oil, decaying grass), paint, or toxic cleaning chemicals — the air in a garage is usually not very healthy air.

But just like with crawl spaces, air does flow from the garage to the house. Only the newest of modern homes — that are using products like ZIP sheathing — are able to fully air seal a garage from the inside of the house.

What this means is: Pay attention to the state of the garage. Which rooms are next to — or worse, above — the garage (air often rises up)?

Detached garages are theoretically superior to attached garages (because they transfer no garage air to the indoor space), but if an attached garage is your only option, it’s not the end of the world.

This is yet another example where “age of the building” comes into play: a younger garage will have less time for chemical spills, rodent nests, and other things that affect air quality. Concrete is not just absorbant of water, it’s also porous for smells. Some smells will almost never come out of a concrete garage floor without being sealed.

Finally, hard surfaces are infinitely more cleanable than carpets.

Carpets are installed because they are cheap. They are replaceable by landlords. They save money for builders.

But carpets also are virtually impossible to, really, truly, actually clean. After you quickly clean your hard floor, it will be 99% cleaner than a carpet.

That’s a big deal!