Each person is different. There is no diet that works for everyone.

Which is another way of saying there’s no perfect diet. And there’s certainly no diet that heals all illness.

There just isn’t one way to eat — one that if we could just figure out — all problems would disappear.

If there were one diet that healed all illness, someone would have identified it already — and every person who tried it would be healed, completely.

Each culture has its own food, with regional plants and animals, and ways to prepare and season meals — all developed over centuries and millenia, specific to each region, to each gene pool, to unique soil types, with endless iterations of weather and climate.

Each human has a truly unique gut microbiome, genetics, learned habits, with an ever-changing assortment of environmental, interpersonal, and life stressors.

So no matter the diet, how efficiently can your body can turn it to energy (which is to say, how well it extracts electrons from food)?

The food-to-fuel process depends on many, many factors:

No single diet can address all of those variables, for each person, for all time.

What’s more, so many diets are based on deprivation. This ignoring of your cravings — fighting the body’s internal cues through sheer will power — is a dangerous game that can disconnect you from your body’s intuition about what it needs to survive and be healthy.

After all, when the body’s cues are squelched long and hard enough, they can go radio silent. The body has a wisdom about what it needs.

You need to find the diet that works best for you — in this moment.

It may be a different diet, right now, than what you’ll find works later — in the future as you recover. As gut health improves, restricted diets often open up to more diversity.

There’s simply no need to commit to one diet forever, so find what works today. You don’t need to answer an eternal question about your diet, just a right now one.

As you improve, you’ll continue to find what works for you tomorrow.

Most healing approaches take the same view on this: avoid lots of food groups: avoid carbs, avoid animal products, avoid fat — you name it, people are avoiding it.

To varying results.

However, few healing modalities speak of the importance of supporting the body’s recovery through sufficient caloric intake.

It’s rare to hear about the dangers of undereating.

Especially considering the years-long focus on caloric restriction which, as a theory, is beginning to falter as researchers continue to study it.

Lowering calories too much has the unfortunate side effects of lowering immunity, creating nutrient deficiencies, weakening bones, harming sleep, and slowing the metabolism.

It’s critical that the body has enough energy to meet its energetic requirements at all times.

What’s worse, the ongoing inflammation of chronic illness alone causes higher caloric requirements.

When inflammation is present, excessive calories are required simply to meet the body’s energetic demands.

Typically, an extra 10-15% above normal daily caloric intake is sufficient to meet caloric needs — when meals are well-balanced.

It’s important to understand that additional calories are needed because the body has become malnourished due to stress, poor diet, or inflammation and cannot, for the time, harvest energy from food efficiently.

Overfeeding also is a means of boosting a slow metabolic rate: More energy in, more energy burned — some see a 40% boost in metabolism from overeating.

The first step, then, is to eat enough food to avoid nutritional and energetic deficiency.

I did this for many, many years — never undereating.

When I underate, my primary symptom was powerful fatigue and insomnia. An additional 20% extra calories per day were enough to stave off the worst of these symptoms.

When the body is starving for energy it uses stress hormones (glucagon, cortisol, adrenaline) to raise blood sugar. These hormones interfere with sleep, make it difficult to relax, and disrupt healthy energy metabolism.

Therefore, eating sufficient calories — plus a little extra — is an important way to stave off the stress hormones of malnutrition, while also addressing malnutrition, itself.

However — can eating sufficient calories heal chronic illness on its own? For most people, no.

For most, additional steps need to be taken, beyond extra calories.

When gut health improves, inflammation can fall and nutrients are efficiently absorbed. The requirement for excessive calories lessens.

When the body requires fewer calories, it means the body has begun absorbing nutrition efficiently.

Among the most important steps to efficiently absorb nutrients? Find an optimal macronutrient ratio.

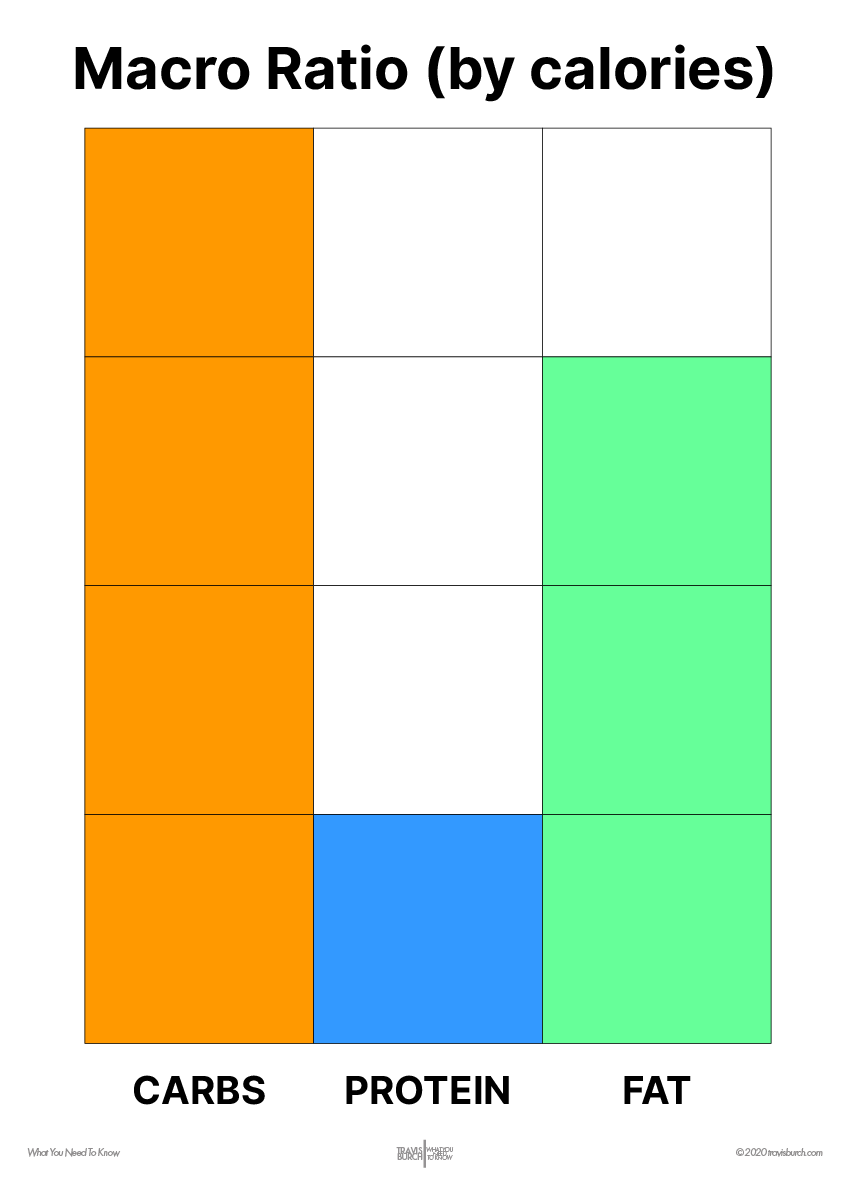

The macro-nutrients are:

…and they require balance between them.

How much of these eaten — per meal, or per day — determines your macro ratio.

For Years, High Carbs

Throughout the healing process, my diet was high in carbohydrates, low in protein, and high fat.

My fiber tolerance was quite low, so I ate very little — only a few bites of carrot per day. The fiber in the carrots helped maintain a bare minimum of bowel function — keeping me regular and removing toxins — even while my digestive function was poor.

During this time, I often ate three to five times more carbs than protein (a 3:1 ratio or higher), to keep my blood sugar up. Any fewer carbs than that would cause my blood sugar to drop. Protein, in particular, caused blood sugar to drop fast.

Falling blood sugar (hypoglycemia) is common when the metabolism has slowed and the stress hormones are exhausted. It typically takes some years of a poor diet, poor gut health (an infectious and toxic state), or “running on stress” for the adrenals to be depleted and hypoglycemia to become a reality.

High Carb/Fat — Low Protein/Fiber

When I was high carb & high fat — and low protein & low fiber — the macro ratio was something around 5:1:4 (C:P:F).

This ratio is not perfect for everyone, but it does address hypoglycemia quite well. It also works okay when fiber and protein tolerance are poor.

In hyperglycemia (diabetes-like situations), a 1:1 carb-to-protein ratio makes much more sense because the blood glucose is not at risk of falling too low.

Going too low in carbs still may be undesirable in many hyperglycemic situations, though — the body may still attempt to raise blood glucose by elevating stress hormones.

A 2:1:1 macro ratio (carbs : protein : fat), by calories, is a solid, balanced place to start.

Carbs are the body’s main source of fuel.

The main sources of carbohydrate that I eat include:

Starch makes up about 60% of my carbohydrate intake — with the rest from sugar sources like honey, fruit, milk, and some sweets (milk chocolate, in particular).

Nearly all my gluten intake is organic.

This reduces exposure to glyphosate (RoundUp) — which interferes with the role of glycine in the body, impairs liver detoxification, kidney function, and manganese absorption.

Fiber shouldn’t count toward carbohydrate totals because fiber does not break down in the gut, nor provide metabolic energy in the form of sugar.

While fiber isn’t absorbed, when fermented by bacteria it does provide nutrients like butyric acid, Vitamin K, and B vitamins.

Not Much Fruit

Ever since a fruitarian phase that lasted several months, fruit has not been high priority (although I did try loads of orange juice on the Ray Peat diet for some time, and it did not yield results).

The fruitarian diet is known to cause serious gut issues that can be difficult to overcome. The Ray Peat diet can cause this to happen as well from high fruit juice and high white sugar intake.

The high potassium in fruit may be an issue for some, lowering blood sugar and sodium levels. It may also deplete Vitamin A.

Protein is a confusing macronutrient in chronic illness.

Sometimes meat is poorly tolerated — other times, it’s the only food tolerable food around.

Is meat healthy — or should we avoid meat?

Protein quality can refer to both amino acid profile and the way an animal was raised.

My Protein Sources

I vary my protein sources equally, rotating through the week.

- 1/4 of my daily protein comes from muscle meat,

- 1/4 from Greek yogurt or cheese

- 1/4 from milk

- 1/4 the rest from eggs or Naked Whey protein.

Meat

Dairy Protein

Bone Broth

Eggs

I do not feel the need to balance protein sources perfectly each day. I’ll go a day or two without meat, eggs, or collagen most every week.

Gelatin

Some bone broth and gelatin is helpful in most cases, but there’s no reason to go overboard with it.

A little here and there is usually enough.

More than 5g per day of gelatin or collagen powder can cause gut problems in some people, as well as glutamate issues and sleep problems — especially when hydrolyzed.

Get A Variety

Mix up protein sources so that you’re not eating the same amino acid profile day after day.

Doing so could lead to slight imbalances in your amino acid profile over time. I rotate through the week with muscle meats, dairy protein, eggs, and a small amount of gelatin.

6+ Years Of High Fat

After being raised on a low-fat diet (as was typical the American ’90s), for the past 6-7 years I’ve eaten much more fat in the diet.

Every few months, I’ll lower my fat intake to see how it affects me. Every time I do this, I’m able to go longer and longer feeling okay — but I always seem to return to a more moderate/high fat intake.

Fat has long helped me feel full and more comfortable. It’s also consistently helped me fall and stay asleep — with its long-lasting energy and calming effect on the gut.

When digestion is poor — and nutrients are poorly absorbed — it’s quite possible for the body to become deficient in both saturated and unsaturated fatty acids.

Fats are also, generally, quite antimicrobial — meaning they can help settle the bad microbes in the gut.

If you don’t tolerate fatty goods, don’t force it — this could indicate several conditions including: gut dysbiosis, a sluggish liver, and more.

Fat Sources

When I eat fat, most of it comes from:

- Whole milk

- Butter

- Olive oil

- Cocoa butter

These days, olive oil has become more prevalent in the diet. It’s often a staple at dinnertime.

I strictly avoided PUFA for many years, but now I don’t fear it from quality sources like fish, high-grade olive oil, and a few other whole-food sources. While I believe PUFA intake is best kept moderate, I also believe 1) the omega-3 to -6 ratio does matter, 2) some PUFA is essential for robust health, and 3) what’s most important is that adequate fat-soluble vitamins are supplied rather thatn complete avoidance of PUFA. When I go too low in PUFA, I feel worse — and I repeatedly feel better incorporating some back into the diet.

Folks with poor digestive health often struggle to tolerate much fiber.

Formerly, Low Fiber

For years, a few bites of raw carrots at each meal was my fiber intake. This small amount of good, quality carrot fiber kept my tummy happier and kept me regular.

Fiber is critically important to soak up toxins and metabolic waste dumped into the gut from liver detoxification.

Cooking vegetables makes them more tolerable in the gut for many people because the highly-fermentable fibers are broken down to some degree.

Another way to get more fiber is to eat fiber in-between meals. This is especially beneficial when fiber is poorly tolerated.

What makes fiber intolerable? The fact that it’s fermentable.

On one hand, good gut microbes — in the presence of a healthy gut with a strong immune system — do not overferment fiber.

On the other hand, bad microbes — in the presence of a weak immune system — act up in the presence of fiber.

- ‘Good’ microbes release vitamins and nutrients after fermenting fiber.

- ‘Bad’ microbes release toxins after fermenting fiber.

Unfortunately, most “healthy” foods are high in fiber — meaning, an unhealthy gut often struggles to digest a normal, healthy diet. The gut must be restored so that healthy foods can be tolerated again.

Now, Lots Of Fiber

As my gut health has improved, tolerance for fiber has risen dramatically.

I now feel best when I eat a very normal, medium-to-high amount of vegetables.

In a healthier gut, a lack of fiber causes bloating, constipation, and poor digestion. When fiber is introduced, those symptoms diminish and digestion is restored.

Excellent, digestible sources of fiber include raw carrots and celery, any cooked vegetable, and fiber supplements such as apple pectin, HMO, or FOS.

As we get healthier, we begin to feel our best eating healthier food.

Progress = Less Restriction, More Variety

We’ll begin to feel better when eating a more varied diet, too — rather than the restrictive diets we were forced to rely on in the past.

This has absolutely been true for me.

As my health has improved, so has my inclination & desire for more varied foods. So, too, have my results after eating more diversity.

In fact, I would now feel much worse eating my old restricted diets.

My new, more balanced diet produces better results than the old restricted diets ever did.

Certainly, the limited diets had a place — when my digestion was poor, restriction was the best I could do. There were lots of foods my gut microbiome, nutritional status, and hypoglycemia disagreed with.

Ultimately, however, fixing my gut (and all the components that entails, such as the circadian rhythm, nutrition, and environmental health) allowed me to move beyond my restricted diet — with better results, more freedom and less stress in my daily life, and better health overall.

After years of tracking, I don’t track macros or calories anymore with an app.

Instead, I mentally estimate where my macros are each day — and listen to my body about what I might need.

Calorie-tracking is essential education, though. If you don’t know what your food has in it, it’s hard to balance your meals and snacks.

After some time balancing macros, it’s easy to transition to a more intuitive style of eating. Even as you eat intuitively, it’s always a good idea to have an basic idea about your macro ratios.

The Cronometer app makes it super easy to learn the nutrient quality of food.

9

Appetite

Your appetite may be a clue into your gut health.

No Appetite? No Health.

A higher appetite is a good thing.

In good health, we eat to satiety and stop. The meal is digested and we become hungry again in time for the next meal. That’s a sign of a functioning metabolism and digestive system.

I actually wasn’t hungry for many years. Zero appetite, ever.

It wasn’t until I fixed my circadian rhythm and ate on a schedule that real, raw animal hunger seemed to kick back in. Even these days, a late breakfast can suppress hunger all day.

The Circadian Rhythm And Meal Timing

Your circadian rhythm is of utmost importance to your appetite — and gut health & metabolism in general.

Eat early in the morning — within 30 minutes of waking up. Eat lunch early instead of late (say: 11:30am). Dinner? Make it a nice, comfortable time — not too late.

When daily activities — especially sleep times and meal times — are aligned for your circadian rhythm, appetite can really pick up.

This is, in part, because the metabolism is being seriously boosted — but also because the gut is working on the schedule it is designed to work on, with appropriate ON/OFF periods of eating and digesting food.

A strong appetite is a sign of a healthy metabolism and digestive system. Having a weak appetite is not a recipe for long-term health. We’ve got to stimulate the digestive fire.

10

A Typical Meal

Always have quick, ready-to-eat staples on hand.

Quick sources of carbohydrate, protein, and fiber that can get you through in a pinch. Group foods into these categories for instant combining into a balanced snack or meal.

A typical meal looks like this:

Carbs

Starch

The main staple of my meals. Starch strongly elevates blood sugar. Around 50-75g of starch.

- SOURCES: Sourdough toast, rice, potatoes, pasta, or oatmeal.

Sugar

About half as much sugar as starch. Usually 25-35g.

- SOURCES: Milk, jam, honey, maple syrup.

Protein

About 40-50g protein per meal. A glass or two of whole milk with most meals adds a bit of protein.

- SOURCES: Meat, Greek yogurt, milk, some cheese

- Slightly less protein at breakfast.

Fat

For some, less fat earlier in the day gives more energy. More fat at night then helps sleep. I eat more fat all day, myself.

- SOURCES: Butter, dairy, olive oil, chocolate

Fiber

For many years, I’ve had a few bites of a raw carrot with most meals. Sometimes I’ll skip the fiber at breakfast, but I usually feel better when I have it.

- 1 carrot or celery stalks (raw)

- 4-7g fiber per meal

I usually take apple pectin (an effective prebiotic fiber) about 90 minutes after breakfast.

Healing the gut is not a two-week process.

Much of our modern discussion about diet — especially with respect to chronic illness — is actually a roundabout discussion of gut health and how that affects immunity, toxicity, sleep, and nutritional status.

The Big Picture

Improving gut health is a many months-long — and certainly a rest-of-your-life — endeavor.

This isn’t unique to the chronically ill, though.

Weakening gut health is a normal part of aging, but it doesn’t have to be. Especially if we can become masters of our gut health after we’ve had a challenge.

The first step to mastery of our gut health? Paying attention, exploring how foods make you feel.

Find the foods that provide more benefit than discomfort — and disregard any commentary by an online heath group or “guru.”

Second, try various macro ratios — always experimenting and watching as gut health responds to the changes.

Third, find a strong gut health regimen that can, over time, greatly influence how well the gut performs and tolerates foods. Combine excellent supplements to synergistically support your gut microbiome.

Focus on things that seemingly aren’t related to gut health: the circadian rhythm, light cycles, nutrient balance, movement, and environmental health (air quality/EMF). All greatly impact the health of the gut.

Over time, we can find ways to improve gut health and, before long, the best, most helpful tactics will become second nature. The diet expands to include more variety — and your body’s ability to process loads of tasty, energizing, nutritious food will be restored.

Read more.